In part one of "The Dark Age?", I took a look at the two films that Disney’s feature animation wing produced following the death of Walt Disney: The Aristocats (1970) and Robin Hood (1973). Both films showed just how misguided the studio was after Uncle Walt’s passing. Executives wanted to play it safe, and the animators didn’t seem to have much freedom, sticking to a formula that was only successful in The Jungle Book. Meanwhile, several animated films from other studios tried new things: George Dunning’s Yellow Submarine, Ralph Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat and Heavy Traffic, and several foreign animated films.

One man was certainly not happy with the situation, it was none other than Don Bluth, who felt that Robin Hood had none of the charm that distinguished Walt Disney’s greatest films, mainly the first five Golden Age gems: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo and Bambi. Bluth balked at the messy storytelling and penny pinching that plagued Robin Hood, and the newly-recruited young animators most likely objected to these problems as well. They were hoping to tackle a project of Snow White’s caliber, not something safe, formulaic and dated. With the next film in production, these animators were ready. In fact, early on, they worked with Don Bluth in his garage on side project called Banjo the Woodpile Cat. This short would be closer to the classic Disney style than what was put out at the time. It was a project that executive Ron Miller, future President of Walt Disney Productions, rejected. A film based on Margery Sharp’s The Rescuers books was a go in the mid-1970s, and it’s one that Don Bluth would be heavily involved it, moving up to the Directing Animator position.

As Disney was working on The Rescuers, more experimental and decidedly adult-oriented animated films came and went. Limited releases of foreign films like Rene Laloux’s Fantastic Planet and several Japanese animated films were common, as they were in the 1960s. Risky endeavors like Richard Williams’ lavish Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure didn’t make a mark at the box office. Television animation studios like Filmation and Hanna Barbera entered the ring with passable efforts like Journey Back to Oz and Charlotte's Web, respectively. The “adult-oriented” animation boom continued as Ralph Bakshi made more films, like the very controversial Coonskin. Other studios tried to ride the wave, with efforts like Once Upon a Girl and Down and Dirty Duck. After Coonskin, Bakshi took a trip into the fantasy genre for his future animated films and dropped the gritty, personal stories. This all began with 1977’s Wizards, which was a rotoscoped film that still got good reviews and did well at the box office as it was certainly more accessible.

The animation scene hadn’t changed much since The Aristocats had come out, Disney’s output was going up against all these kinds of films. In order to really compete, even though Disney’s films won at the box office each time out, they needed to make a film that was worthy of what Walt produced. The Rescuers was most likely conceived as another Jungle Book/Aristocats/Robin Hood-style comedy with the same old routine. Early drafts even had Cruella de Vil as the villain! Don Bluth and the animators wanted something better. The improved Xerography process removed the rough look of the earlier films. Immensely disdainful of the look that Xerography had delivered in One Hundred and One Dalmatians, Walt would’ve been pleased with this since the animators were able to go back to the classic designs while the studio could still cut costs. Colored outlines could now be utilized, making things look noticeably softer than what was seen in everything from Dalmatians to Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too! (1974).

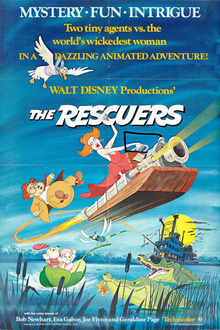

The Rescuers’ story involved a young orphan girl named Penny (voiced by Michelle Stacy), who is held captive on a riverboat in the Southern bayous by an unscrupulous woman named Madam Medusa (voiced by Geraldine Page) and her bumbling, inept partner, Mr. Snoops (voiced by Joe Flynn). They use the poor girl to search a pirate’s cave for an elusive diamond called the Devil’s Eye. The Rescue Aid Society, a brigade of noble mice from all around the world get her message in a bottle and send the timid janitor Bernard (voiced by Bob Newhart) and the adventurous Miss Bianca (voiced by Eva Gabor) on a mission to save her and bring her back to Morningside Orphanage in New York. Without anyone like Don Bluth around, this could’ve easily been another unmitigated disaster on the order of Robin Hood. Bluth made sure that the story would be told the way Walt would’ve told it, with drama, depth and darkness while also having enough comic relief to take the edge off when appropriate. The Devil’s Bayou, the swamp where most of the film takes place, is very gloomy and dark. The scene where Penny, with the help of Bernard and Bianca, tries to get the diamond out of a skull inside the pirate’s cave before it floods is wonderfully tense. Madam Medusa is also one of Disney’s most unfairly overlooked villains, a mean-spirited character who actually goes out of her way to really hurt Penny’s feelings (“What makes you think anyone would want a homely little girl like you?” she says to her after Penny tells her why she wants to go back to the orphanage after she finds the diamond). Animated with such flamboyance by Milt Kahl, she is actually a much better antagonist than a good number of Disney’s most well-known and loved villains. She manipulates the girl while treating her terribly, all to get ahead and get something she wants. This is a much better conflict than what we saw in the previous couple of films, as we really root for Penny’s escape and for the two mice to succeed in their mission.

Going against the darkness and the unusually strong conflict is yet again more silliness in the form of a gang of swamp critters who are of help to the two mice. They have a point in the story, but their antics mimic the comedy we saw in Robin Hood (not to mention some of the cast is straight out of that film). This isn’t a bad thing, but at times it tends to clash with the overall mood of the narrative. Slapstick is there, too, sometimes going against the dark tone of the story, such as Medusa’s gun being clogged with a stick of dynamite that backs up like it was its own character. In a more successful slapstick moment, a scene where Bernard and Bianca try to get away from Brutus and Nero (Medusa’s alligators) in a pipe organ is absolutely hilarious. Orville, the albatross who flies Bernard and Bianca from New York to down South, is a hoot. Voiced by Fibber McGee himself, Jim Jordan, the funniest bits are the scenes where he avoids Medusa’s fireworks on the way to the bayou.

The only other problems with The Rescuers are in the animation itself. While the character animation is fantastic, the film still has a lot of roughness. Animation from past films is recycled once again, especially on an important sequence like “Someone’s Waiting for You”. Rotoscoping is also used, from special effects (which are either subtle or jarring) to human characters we only see for mere seconds. Some backgrounds are also borrowed, such as a shot of the Devil’s Bayou which takes the same set of trees from The Jungle Book. That is actually followed by a scene where Penny runs away, it’s the same animation of Mowgli running away from Baloo when he tells the boy that he has to go back to the man village. Again, laziness. The entire opening credits is told through paintings by Mel Shaw, which are beautiful, and make up for the opening credits of The Aristocats and Robin Hood, which basically recycled scenes from the film itself.

The songs are good for the most part. All but one of them are sung offscreen, much like Dumbo and Bambi, and written by Carol Connors, Sammy Fain (who wrote songs for Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan) and Ayn Robbins. “Someone’s Waiting for You” is a tearjerker, but it is only undermined by the use of recycled animation (Bambi’s mother, for instance), but that wouldn’t be much of a nuisance to a non-animation fan. “Tomorrow is Another Day” is pretty, but it has a dated 1970s pop twang to it. “The Journey” is absolutely beautiful, and the artwork its set to makes it all the more better. The only song that I could do without is “Rescue Aid Society”, a silly, forgettable tune that’s the only number that the characters sing.

The Rescuers, despite some setbacks, was a return to form. Gone was the slapdash storytelling seen in The Aristocats and Robin Hood. The film did its best to cater to adults and everyone else, rather than the younger set, much like the classics did. Its mix of action, inspired art direction, very good writing and a strong story made for an entertaining event that no one should’ve missed. This film would solidify why Disney animated films were worth seeing on the big screen, and with the quality of the story behind it, it could compete with the heavies at the box office.

The Rescuers opened in the summer of 1977 to rave reviews all across the board, with many critics praising it as a sort of “second coming”. This is all thanks to the ambitions of Don Bluth and the enthusiastic young crew working on the film, as many animators such as Milt Kahl made this film their swan song. The Rescuers was also a huge hit at the box office, becoming the highest grossing animated on initial release. The record wouldn’t broken for another nine years. All seemed well in the world of animation, Disney had finally gotten back to their roots and soared critically and commercially at the same time. Disney immediately fired up production on the next film, The Fox and the Hound and also sought to jumpstart a film based on Lloyd Alexander’s The Chronicles of Prydain, as the project based on the five-book series had been in pre-production earlier that decade. Meanwhile, Don Bluth and the animators were finishing up on Pete's Dragon and working on a short subject called The Small One. Another upcoming project was Mickey's Christmas Carol, based on Charles Dickens’ classic featuring Scrooge McDuck as Ebenezer Scrooge.

Problems began to rise during production of The Fox and the Hound. Bluth and several of the other animators objected to Disney’s cost-cutting methods and their adherence to a formula. Story changes were made that compromised this adaptation of Daniel P. Mannix’s downer novel, which was being tooled into a story that was about prejudice. That was one of many problems that ultimately lead to Don Bluth resigning on September 14, 1979 with fourteen of the young animators. This was a harsh blow to Disney, and it even made the news, which was rare in the world of animation at the time. With that, Disney immediately delayed the release of the film from a Christmas 1980 date to the summer of 1981. The company did what they could to blacklist Bluth and the former animators, who had completed Banjo the Woodpile Cat and were joining forces with Aurora Productions (formed by former Disney executives) to produce a full-length feature film to compete with Disney’s films.

With the rest of the veteran animators retiring, Disney started recruiting more animators and improved the training program. Production moved forward once again, but the story had already been compromised from the get-go. Due to these problems, The Fox and the Hound was a step backwards from The Rescuers. The story centered around a fox kit named Tod (young Tod is voiced by Keith Coogan, and adult Tod is voiced by Mickey Rooney) and a hound puppy named Copper (Corey Feldman provides the voice of young Copper, while Kurt Russell provides his adult voice), who become inseparable friends. Unfortunately, Copper is supposed to grow up to become a hunting dog and Tod’s adoptive owner, Widow Tweed (voiced by Jeanette Nolan), will have to release him in the wild one day. Copper’s trigger-happy owner, Amos Slade (voiced by Jack Albertson), already doesn’t take a liking to the mischievous fox cub. Meanwhile, an owl named Big Mama (voiced by Pearl Bailey) attempts to help Tod understand that Copper may have to hunt him down one day.

Fortunately, the story isn’t episodic like Robin Hood’s lazy excuse for a narrative and the writing for the most part is passable. The characters are appealing, and there’s an unusually melancholic tone that permeates the entire film. Punches are pulled, hurting the story in many ways. When director Art Stevens demanded that Chief should’ve survived after getting hit by the train, he not only watered down the story but he also went against logic. Chief not dying after that accident was terribly unrealistic, and Copper’s revenge is pointless now that Chief just wobbles around with a broken leg. Despite the holes, the film’s second half is surprisingly intense compared to the rather innocent first act.

Another problem is the excessive cutesiness in the first act, which is blown over the top thanks to the inclusion of two comic relief birds that add nothing to the story. They only exist to provide laughs for the children, once again reminding one of the goofiness of The Aristocats and Robin Hood. Like Robin Hood and The Rescuers, Disney was also perfectly content with casting celebrities who were known for their comedy TV shows. The cast certainly gives it their all, especially Pearl Bailey, who provides the voice of Big Mama, an owl who helps Todd understand things. This sort of thing had become by the early 1980s, however.

The Fox and the Hound's central theme is one of its greatest strengths, as the story of Tod and Copper’s friendship was meant to mirror the lives of children who are raised with racial prejudice in the 1970s. This theme was so prominent that it actually caught the attention of the public upon release. Politics in a Disney film? There were other deep themes in the Disney films of the past, but The Fox and the Hound’s message caught on in the media, and a few critics praised that element of the story. Combine that with its somber mood (a byproduct of Don Bluth’s career at the studio) and some incredible animation, The Fox and the Hound isn’t an outright failure. It’s a film that wants to be right in line with The Rescuers, but it’s held back by executives and misguided minds trying to play it safe. What made The Rescuers work was that it didn’t play it safe, it tried to be like a Walt film with its moody visuals, great heart and solid story. With everything that works against this film, you can see why Don Bluth and the animators left during production. Take this story for example: Wolfgang Reitherman, who already liked the idea of recycling animation from past Disney films, wanted a sequence where Tod and Vixey (voiced by Sandy Duncan) meet two cranes voiced by Phil Harris and Charo. The two were to provide a disco number. Everyone hated the idea, and rightfully so. It would’ve been a painfully pathetic way to make the film relevant, but also, disco wasn’t topping the charts by 1981. As if Art Stevens’ forcing the story team to scrap Chief’s death wasn’t enough... The Fox and the Hound’s second act is riddled with the contrived revenge (again, due to Chief’s death being nixed), a love story that seems like an eleventh hour inclusion and scenes where Tod meets various critters in the forest such as a grumpy old Badger (voiced by John McIntire) and a kindly porcupine (voiced by John Fiedler). The story ultimately plods until its intense third act climax, where Tod and Copper fight to the death. The fight leads up to an encounter with a massive grizzly bear. Glen Keane turned this sequence into a powerhouse of vicious, wild animation and jaw-dropping staging.

Originally, he had planned to animate it in charcoal, but it would prove to be too costly. At the time, this was the most expensive animated film ever made with a budget of $12 million. Yet it doesn’t suggest the quality. While most of the character animation soars, the art direction feels like a milder version of what we saw in older Disney films set in beautiful forests. It’s still nice to look at, but nothing special. It’s got a very soft look that’s closer to the 1950s Disney films than anything, but nothing elaborate or even innovative. The music is forgettable, with awkward songs like “Lack of Education”, where Big Mama and the two comic relief birds attempt to tell Tod about what might happen to him. “Goodbye May Seem Forever” almost reaches tearjerker level, but it’s minimal and ultimately without much of an effect since it goes by too quickly with a weird arrangement and half-baked harmonies. “A Huntin’ Man” only lasts mere seconds. “Best of Friends” is passable at best, if not for Pearl Bailey’s vocals. “Appreciate the Lady”, also sung by Bailey, is also awkward and too short to be a suitable love song. The score’s odd mix of a cheesy 1980s tone and the overuse of the wailing country harmonica is a bit droning, and it affects a lot of these songs.

The Fox and the Hound should not have had musical numbers, because for the first time, it feels as if the crew added songs for the sake of having them in the film. The story didn’t need to be a musical, instead they could’ve opted for just a few songs that were sung offscreen much like the ones in Dumbo, Bambi and The Rescuers. Given the tone of the original novel, this probably wasn’t a suitable story to tackle at Disney at the time. Walt certainly wouldn’t approach the story this way, he would’ve done it in a similar manner to Bambi with less comic relief, enough innocence so it wouldn’t be cloying, and more drama. The film’s climactic bear fight scene is excellent, and it makes the rest of the film seem so pedestrian in comparison. Had the rest of the film been more like that, and no silly humor, contrived songs or annoying comic relief characters, The Fox and the Hound would essentially be the continuation of the ambition seen in The Rescuers.

For the most part, it has great intentions. If not for the misguided nature of the studio at the time, and if not for Don Bluth’s departure, it could’ve been a great and profound film that would get the widespread critical acclaim its predecessor got and perhaps convinced audiences that animation was an art form for adults. It would be Bambi, but for the 1980s. Sadly, it wasn’t meant to be, though a good chunk of the brilliance is kept. This makes The Fox and the Hound an average effort at best, one that’s severely held back from being something truly special. When released in the summer of 1981, it received mixed reviews. Some critics praised the prejudice themes, the animation and a few other things. Others found fault with the cutesiness and how watered down it was. Nevertheless, it was very successful at the box office, outgrossing The Rescuers. With that, Disney fired up production on The Black Cauldron, the long in development project based on the Lloyd Alexander novels. Meanwhile, Don Bluth Productions was hard at work on an ambitious, dazzling animated feature: The Secret of NIMH...

The Rescuers, like the success of Yellow Submarine and Fantasia in the late 1960s, was almost the start of a new renaissance for the art form. Again, it did not happen. Disney went backwards, as competitors continued to move forward. The late 1970s was also a time when Disney started making very interesting creative decisions, but, we’ll save that part three...

With the rest of the veteran animators retiring, Disney started recruiting more animators and improved the training program. Production moved forward once again, but the story had already been compromised from the get-go. Due to these problems, The Fox and the Hound was a step backwards from The Rescuers. The story centered around a fox kit named Tod (young Tod is voiced by Keith Coogan, and adult Tod is voiced by Mickey Rooney) and a hound puppy named Copper (Corey Feldman provides the voice of young Copper, while Kurt Russell provides his adult voice), who become inseparable friends. Unfortunately, Copper is supposed to grow up to become a hunting dog and Tod’s adoptive owner, Widow Tweed (voiced by Jeanette Nolan), will have to release him in the wild one day. Copper’s trigger-happy owner, Amos Slade (voiced by Jack Albertson), already doesn’t take a liking to the mischievous fox cub. Meanwhile, an owl named Big Mama (voiced by Pearl Bailey) attempts to help Tod understand that Copper may have to hunt him down one day.

Fortunately, the story isn’t episodic like Robin Hood’s lazy excuse for a narrative and the writing for the most part is passable. The characters are appealing, and there’s an unusually melancholic tone that permeates the entire film. Punches are pulled, hurting the story in many ways. When director Art Stevens demanded that Chief should’ve survived after getting hit by the train, he not only watered down the story but he also went against logic. Chief not dying after that accident was terribly unrealistic, and Copper’s revenge is pointless now that Chief just wobbles around with a broken leg. Despite the holes, the film’s second half is surprisingly intense compared to the rather innocent first act.

Another problem is the excessive cutesiness in the first act, which is blown over the top thanks to the inclusion of two comic relief birds that add nothing to the story. They only exist to provide laughs for the children, once again reminding one of the goofiness of The Aristocats and Robin Hood. Like Robin Hood and The Rescuers, Disney was also perfectly content with casting celebrities who were known for their comedy TV shows. The cast certainly gives it their all, especially Pearl Bailey, who provides the voice of Big Mama, an owl who helps Todd understand things. This sort of thing had become by the early 1980s, however.

The Fox and the Hound's central theme is one of its greatest strengths, as the story of Tod and Copper’s friendship was meant to mirror the lives of children who are raised with racial prejudice in the 1970s. This theme was so prominent that it actually caught the attention of the public upon release. Politics in a Disney film? There were other deep themes in the Disney films of the past, but The Fox and the Hound’s message caught on in the media, and a few critics praised that element of the story. Combine that with its somber mood (a byproduct of Don Bluth’s career at the studio) and some incredible animation, The Fox and the Hound isn’t an outright failure. It’s a film that wants to be right in line with The Rescuers, but it’s held back by executives and misguided minds trying to play it safe. What made The Rescuers work was that it didn’t play it safe, it tried to be like a Walt film with its moody visuals, great heart and solid story. With everything that works against this film, you can see why Don Bluth and the animators left during production. Take this story for example: Wolfgang Reitherman, who already liked the idea of recycling animation from past Disney films, wanted a sequence where Tod and Vixey (voiced by Sandy Duncan) meet two cranes voiced by Phil Harris and Charo. The two were to provide a disco number. Everyone hated the idea, and rightfully so. It would’ve been a painfully pathetic way to make the film relevant, but also, disco wasn’t topping the charts by 1981. As if Art Stevens’ forcing the story team to scrap Chief’s death wasn’t enough... The Fox and the Hound’s second act is riddled with the contrived revenge (again, due to Chief’s death being nixed), a love story that seems like an eleventh hour inclusion and scenes where Tod meets various critters in the forest such as a grumpy old Badger (voiced by John McIntire) and a kindly porcupine (voiced by John Fiedler). The story ultimately plods until its intense third act climax, where Tod and Copper fight to the death. The fight leads up to an encounter with a massive grizzly bear. Glen Keane turned this sequence into a powerhouse of vicious, wild animation and jaw-dropping staging.

Originally, he had planned to animate it in charcoal, but it would prove to be too costly. At the time, this was the most expensive animated film ever made with a budget of $12 million. Yet it doesn’t suggest the quality. While most of the character animation soars, the art direction feels like a milder version of what we saw in older Disney films set in beautiful forests. It’s still nice to look at, but nothing special. It’s got a very soft look that’s closer to the 1950s Disney films than anything, but nothing elaborate or even innovative. The music is forgettable, with awkward songs like “Lack of Education”, where Big Mama and the two comic relief birds attempt to tell Tod about what might happen to him. “Goodbye May Seem Forever” almost reaches tearjerker level, but it’s minimal and ultimately without much of an effect since it goes by too quickly with a weird arrangement and half-baked harmonies. “A Huntin’ Man” only lasts mere seconds. “Best of Friends” is passable at best, if not for Pearl Bailey’s vocals. “Appreciate the Lady”, also sung by Bailey, is also awkward and too short to be a suitable love song. The score’s odd mix of a cheesy 1980s tone and the overuse of the wailing country harmonica is a bit droning, and it affects a lot of these songs.

The Fox and the Hound should not have had musical numbers, because for the first time, it feels as if the crew added songs for the sake of having them in the film. The story didn’t need to be a musical, instead they could’ve opted for just a few songs that were sung offscreen much like the ones in Dumbo, Bambi and The Rescuers. Given the tone of the original novel, this probably wasn’t a suitable story to tackle at Disney at the time. Walt certainly wouldn’t approach the story this way, he would’ve done it in a similar manner to Bambi with less comic relief, enough innocence so it wouldn’t be cloying, and more drama. The film’s climactic bear fight scene is excellent, and it makes the rest of the film seem so pedestrian in comparison. Had the rest of the film been more like that, and no silly humor, contrived songs or annoying comic relief characters, The Fox and the Hound would essentially be the continuation of the ambition seen in The Rescuers.

For the most part, it has great intentions. If not for the misguided nature of the studio at the time, and if not for Don Bluth’s departure, it could’ve been a great and profound film that would get the widespread critical acclaim its predecessor got and perhaps convinced audiences that animation was an art form for adults. It would be Bambi, but for the 1980s. Sadly, it wasn’t meant to be, though a good chunk of the brilliance is kept. This makes The Fox and the Hound an average effort at best, one that’s severely held back from being something truly special. When released in the summer of 1981, it received mixed reviews. Some critics praised the prejudice themes, the animation and a few other things. Others found fault with the cutesiness and how watered down it was. Nevertheless, it was very successful at the box office, outgrossing The Rescuers. With that, Disney fired up production on The Black Cauldron, the long in development project based on the Lloyd Alexander novels. Meanwhile, Don Bluth Productions was hard at work on an ambitious, dazzling animated feature: The Secret of NIMH...

The Rescuers, like the success of Yellow Submarine and Fantasia in the late 1960s, was almost the start of a new renaissance for the art form. Again, it did not happen. Disney went backwards, as competitors continued to move forward. The late 1970s was also a time when Disney started making very interesting creative decisions, but, we’ll save that part three...

No comments:

Post a Comment