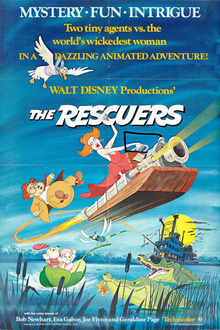

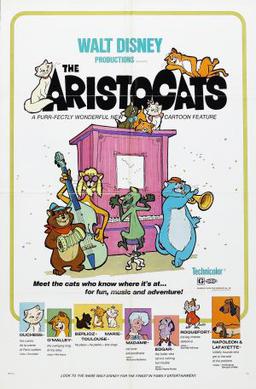

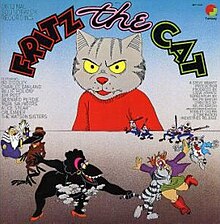

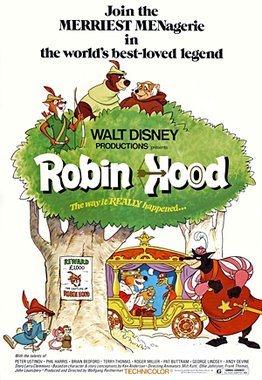

Don Bluth’s departure from Disney in September of 1979 was certainly a devastating blow to the troubled animation studio. Upon arrival, he was instrumental in shaping The Rescuers, which went from potential disaster to Disney’s biggest hit and the highest grossing animated film on initial release at the time. Don Bluth wanted to bring back the classic storytelling to Disney animation, something that was not on display in The Aristocats and Robin Hood, which were cheap, often lazy films that kept the animation studio alive.

Bluth stormed out of the studio during production of The Fox and the Hound, which wouldn’t garner the praise that The Rescuers got but was a box office success. More animators were brought on board after Bluth left with fourteen other animators, and they were put to work on safer projects such as Mickey's Christmas Carol before moving onto the ambitious debacle that would be The Black Cauldron.

Now what if Don Bluth never left? What if he was able to fight the management and bring Disney animation back to the glory days? Perhaps the Second Golden Age would’ve started with The Rescuers and flourished from there...

The autumn of 1977...

The Rescuers was a massive hit at the box office over the summer and got the best reviews for a Disney animated film since One Hundred and One Dalmatians. It is a triumphant success, one that even outgrosses Star Wars in some European markets. It has a better storyline, better writing, and better animation that what was seen in the previous two films. (Not counting The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, released earlier that year.)

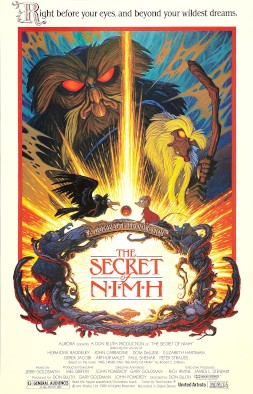

The conservative management at Disney sees the potential the new animators can bring to the table, as production wraps on more training vehicles like Pete's Dragon and The Small One. Production on The Fox and the Hound, an adaptation of a novel by Daniel P. Mannix, begins immediately. Next in line is an adaptation of Lloyd Alexander’s The Chronicles of Prydain series, which Disney had the rights to since 1971. Other projects such as an adaptation of Robert O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH are also considered, along with an adaptation of Chanticleer, which was canned by Disney back in 1960.

Wolfgang Reitherman prepares treatment for The Fox and the Hound and presents it to the story crew and animators in early 1978. While it does have some good ideas, it is overall reminiscent of Robin Hood, with goofy Southern characters, cutesy moments and a corny disco number to be sung by Phil Harris and Charo. All of the animators, and even the management object to this. Wolfgang Reitherman retires shortly after, Don Bluth reshapes the story and keeps a few elements from Woolie’s treatment.

Coverage surrounds the production of the film, unheard of in the animation world. $12 million goes into the production, making it the highest for an animated feature film. Meanwhile, Disney searches for other talent for their live-action output. Don Bluth changes the Robin Hood-esque story into one that’s more in line with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, with occasionally dark and frightening moments for the younger set. It also has a strong message about prejudice, made more front-and-center than it was in Woolie’s version. Oddly enough, it’s no happily ever after ending, as it has a more bittersweet ending while it’s nowhere as harsh as it was in the book.

The Fox and the Hound is completed in time for its planned holiday 1980 release. The marketing plays up the darker angle of the story. Disney had ventured into the PG territory for their live action fare, though The Fox and the Hound would still get a G rating. The child-friendly marketing focused on the scenes with young Tod and Copper, while the general marketing played down the cutesy elements.

Reaching a Bigger Audience

The Fox and the Hound opens on December 12, 1980 to critical praise all across the board. It’s called “Bambi for the current generation”. Critics praise the dark and often moody story, while also admiring the animation. It also isn’t a musical, though there are some songs sung off-screen that get some acclaim. With that, Roy Disney comes to the studio and makes sure the management can hold everything together. The Fox and the Hound takes in $91 million and dents the Top 5.

Production begins on The Black Cauldron, the planned adaptation of The Chronicles of Prydain. Don Bluth, along with the new team of animators, work two books into one story while also ironing out the bugs and glitches. The film is scheduled for release in 1983. What better way to do an epic fantasy but through the power of Disney animation? The team are determined to really live up to the ambitions of Walt Disney with this film, and rival the likes of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio and Fantasia. A budget of $25 million is secured, trumping The Fox and the Hound.

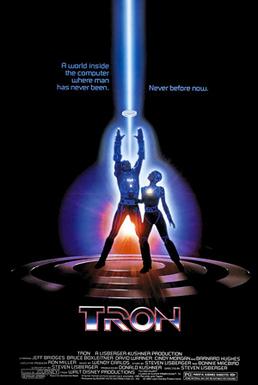

Other animation studios resort to producing cheap toy commercials, though some artistic films caught on such as Twice Upon a Time and The Plague Dogs. While The Black Cauldron is well into production, Tron is released. An advancement for computer generated imagery, the animators use these new tricks for The Black Cauldron, as Don Bluth favors effects. A young John Lasseter is also highly interested, doing a test scene with Glen Keane for the potential next film at Disney: Where the Wild Things Are. With these kinds of effects, The Black Cauldron could compete with the big budget heavies for the year, mainly Return of the Jedi. The film is also done in APT, which replaces the scratchy look of Xerography, and makes for a much cleaner-looking picture with better clean-up animation work. It's a step up from The Rescuers and The Fox and the Hound, which use a softened version of Xerography that uses colored lines.

The Black Cauldron opens on July 22, 1983. It is the first Disney animated film to receive a PG rating from the MPAA for scary imagery, dark moments, some brief language and some unexpected bloody violence. This was the new Disney, more adult-oriented while still suitable enough for family audiences. The marketing is aggressive, selling it as a big fantasy epic and one to really take off at the box office, and it did. On top of unanimous praise, the film grossed $145 million domestically and over $300 million worldwide. It was the second biggest film of the year behind Return of the Jedi and the highest grossing animated film on initial release. Its final total even surpasses Snow White’s unadjusted totals plus all of its re-releases. Disney animation was heading into a new frontier, a Renaissance...

The next release is extremely successful: The Secret of NIMH opens in 1986 to great reviews and grosses over $100 million stateside and $250 million worldwide. Like The Black Cauldron, it’s a dark, effects-heavy and compelling fantasy film. It is clear by this point that Disney animation has entered a Renaissance, while other studios see that animation is a hot property. Warner Bros., Fox, MGM and Paramount all take notice. The Secret of NIMH also uses a prototype version of CAPS (Computer Animation Production System), which allows the artists to digitally ink and paint their drawings. It singlehandedly replaces APT, and now the Disney animated features can look as polished as the Golden Age features. This makes big news in the film world.

Ambition

Plans for a Black Cauldron sequel are also a go, since there are a few books left to adapt. Howard Ashman and Alan Menken, fresh off of Little Shop of Horrors, are called in to help do a musical adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, a return to the fairy tale genre and a project Walt Disney once looked into. Ron Clements and John Musker are named directors of the project. Other animators and writers are given shots to direct a feature film. CAPS makes it easier for the experienced animators to get an animated film out every 1-2 years.

It goes the way Walt Disney had always intended, before World War II put a stop to his plans. The idea of doing one animated feature a year was his dream before the financial failures of Pinocchio, Fantasia and Bambi. Since the Disney studios are alive through the live-action fare, the theme parks and the revenue of the re-releases, they are able to go through with this plan.

After The Secret of NIMH hits theaters, the animators begin full production on an original story by Don Bluth, The Land Before Time. He envisions the story as a silent, Fantasia-esque tale about prehistoric life. A year earlier, Disney joins forces with animator Richard Williams, director Robert Zemeckis and producer Steven Spielberg to bring forth Who Framed Roger Rabbit, which is to be shot in live action while the Toon Town characters are done in animation. A $50 million budget is secured and production begins, as it is scheduled for release in 1988. The Land Before Time is also scheduled for release that year.

In early 1987, Disney releases The Secret of NIMH on home video, the first contemporary film to be released on the format as Disney had been slowly rolling out the classics: Pinocchio, Dumbo, Alice in Wonderland, Sleeping Beauty, The Sword in the Stone and Robin Hood, from 1984 to 1986. While those titles sold very well, NIMH sells an unprecedented 5 million copies on VHS, Betamax and LaserDisc. From there, Disney decides to release them on home video after the theatrical release, rather than wait and re-release it in theaters. The home video is a new world by this point.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit opens on June 24, 1988 to widespread critical acclaim. The film is even more adult-oriented than Disney's recent fare, as it really catches on with the teenage audience. It grosses $296 million stateside and $604 million worldwide. It is a watershed moment for American feature animation. In return, Robert Zemeckis and Steven Spielberg agree to help Richard Williams finish his long-in-production animated feature, The Thief and the Cobbler. Full production begins in late 1988 for a projected 1990/1991 release, for Warner Bros. first new animated feature release. The studio also acquires a pet project by comedian Rodney Dangerfield, an R-rated animated comedy titled Rover Dangerfield.

The Land Before Time opens months later on November 18th, to yet again critical acclaim and grosses $178 million stateside and $356 million worldwide. It is also a groundbreaker, being the first animated feature done in CAPS, which Disney tested for NIMH. It gets a few Academy Award nominations here and there, drawing enthusiasm for the next batch of animated films. The home video release comes in May 1989, 8 million units are sold.

The upcoming schedule is ramped up yet again. Following the release of The Little Mermaid in fall 1989 will be The Rescuers Down Under in fall 1990, followed by Beauty and the Beast for 1991, Aladdin for 1992 and a project tentatively titled King of the Jungle for release in 1993. Other ideas are currently kicked around: A Black Cauldron sequel, Thumbelina, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, a new Fantasia and a slew of smaller-budget films based on their current animated television shows such as DuckTales and Chip 'n' Dale Rescue Rangers.

Ron Clements and John Musker work with a strong story for The Little Mermaid, which is backed by Broadway-style songs by Howard Ashman and Alan Menken. A surefire cast and the current techniques also sharpen The Little Mermaid's story, though the writers did change the original fairy tale's downer ending. The Little Mermaid opens on November 17, 1989. It is surrounded with widespread critical acclaim, and it even gets nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards. The film makes a grand total of $270 million domestically and $535 million worldwide. It is the next big step for Disney's feature animation division, which announces its new name, Walt Disney Animation Studios. The Little Mermaid hits home video in May 1990, 10 million units are sold, making it the second best-selling home video release of all time behind Steven Spielberg's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

John Lasseter sets up a computer animation division with Ed Catmull, Steve Jobs and alumni from CalArts, after experimenting with it for independent short films like Luxo Jr. and Tin Toy, and calls it Pixar. It's set up to deliver computer animated releases alongside Disney's traditional animation films. Production begins on a Tin Toy Christmas special, which is later blown up into a feature-length film.

Prior to the release of The Rescuers Down Under, which has consultants from Pixar on board, Disney theatrically re-released The Rescuers in theaters in the spring of 1988. On this re-release, it took in $40 million while also including a trailer that had early test footage of the sequel. The Rescuers is then released on home video in June 1989, and sells a whopping 7 million units. Anticipation fires up for the sequel, as the video release reminds audiences how good the film was.

The Rescuers Down Under didn't exactly repeat the success of The Little Mermaid when released on November 16, 1990, but it took in $133 million stateside and $267 million worldwide. Reviews were also good, while some critics had problems with the more action-oriented approach to the story rather than the slow, heartfelt one taken with the first film. The use of computer generated imagery and effects told the story the way the animators had seen it, and it was a blast to experience. It is also the first Disney animated feature to be exhibited in IMAX theaters.

Warner Bros. becomes to the first big competitor to the reborn Disney, just as they were the big competition to Disney during the Golden Age, with the release of Richard Williams' The Thief and the Cobbler, featuring dazzling animation all painstakingly done by hand. Critics gush over the visuals, but also criticize the often stuffed story and lack of heart. Regardless, it is a milestone for feature animation. It opens the same day as The Rescuers Down Under and puts up a good fight, grossing $102 million domestically and $244 million worldwide. Disney takes note of this and retools Aladdin to be more of an irreverent comedy. It was the first head-to-head match in the world of animation, and it receives widespread coverage all across the board.

It goes the way Walt Disney had always intended, before World War II put a stop to his plans. The idea of doing one animated feature a year was his dream before the financial failures of Pinocchio, Fantasia and Bambi. Since the Disney studios are alive through the live-action fare, the theme parks and the revenue of the re-releases, they are able to go through with this plan.

After The Secret of NIMH hits theaters, the animators begin full production on an original story by Don Bluth, The Land Before Time. He envisions the story as a silent, Fantasia-esque tale about prehistoric life. A year earlier, Disney joins forces with animator Richard Williams, director Robert Zemeckis and producer Steven Spielberg to bring forth Who Framed Roger Rabbit, which is to be shot in live action while the Toon Town characters are done in animation. A $50 million budget is secured and production begins, as it is scheduled for release in 1988. The Land Before Time is also scheduled for release that year.

In early 1987, Disney releases The Secret of NIMH on home video, the first contemporary film to be released on the format as Disney had been slowly rolling out the classics: Pinocchio, Dumbo, Alice in Wonderland, Sleeping Beauty, The Sword in the Stone and Robin Hood, from 1984 to 1986. While those titles sold very well, NIMH sells an unprecedented 5 million copies on VHS, Betamax and LaserDisc. From there, Disney decides to release them on home video after the theatrical release, rather than wait and re-release it in theaters. The home video is a new world by this point.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit opens on June 24, 1988 to widespread critical acclaim. The film is even more adult-oriented than Disney's recent fare, as it really catches on with the teenage audience. It grosses $296 million stateside and $604 million worldwide. It is a watershed moment for American feature animation. In return, Robert Zemeckis and Steven Spielberg agree to help Richard Williams finish his long-in-production animated feature, The Thief and the Cobbler. Full production begins in late 1988 for a projected 1990/1991 release, for Warner Bros. first new animated feature release. The studio also acquires a pet project by comedian Rodney Dangerfield, an R-rated animated comedy titled Rover Dangerfield.

The Land Before Time opens months later on November 18th, to yet again critical acclaim and grosses $178 million stateside and $356 million worldwide. It is also a groundbreaker, being the first animated feature done in CAPS, which Disney tested for NIMH. It gets a few Academy Award nominations here and there, drawing enthusiasm for the next batch of animated films. The home video release comes in May 1989, 8 million units are sold.

The upcoming schedule is ramped up yet again. Following the release of The Little Mermaid in fall 1989 will be The Rescuers Down Under in fall 1990, followed by Beauty and the Beast for 1991, Aladdin for 1992 and a project tentatively titled King of the Jungle for release in 1993. Other ideas are currently kicked around: A Black Cauldron sequel, Thumbelina, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, a new Fantasia and a slew of smaller-budget films based on their current animated television shows such as DuckTales and Chip 'n' Dale Rescue Rangers.

Topping The Charts

Ron Clements and John Musker work with a strong story for The Little Mermaid, which is backed by Broadway-style songs by Howard Ashman and Alan Menken. A surefire cast and the current techniques also sharpen The Little Mermaid's story, though the writers did change the original fairy tale's downer ending. The Little Mermaid opens on November 17, 1989. It is surrounded with widespread critical acclaim, and it even gets nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards. The film makes a grand total of $270 million domestically and $535 million worldwide. It is the next big step for Disney's feature animation division, which announces its new name, Walt Disney Animation Studios. The Little Mermaid hits home video in May 1990, 10 million units are sold, making it the second best-selling home video release of all time behind Steven Spielberg's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

John Lasseter sets up a computer animation division with Ed Catmull, Steve Jobs and alumni from CalArts, after experimenting with it for independent short films like Luxo Jr. and Tin Toy, and calls it Pixar. It's set up to deliver computer animated releases alongside Disney's traditional animation films. Production begins on a Tin Toy Christmas special, which is later blown up into a feature-length film.

Prior to the release of The Rescuers Down Under, which has consultants from Pixar on board, Disney theatrically re-released The Rescuers in theaters in the spring of 1988. On this re-release, it took in $40 million while also including a trailer that had early test footage of the sequel. The Rescuers is then released on home video in June 1989, and sells a whopping 7 million units. Anticipation fires up for the sequel, as the video release reminds audiences how good the film was.

The Rescuers Down Under didn't exactly repeat the success of The Little Mermaid when released on November 16, 1990, but it took in $133 million stateside and $267 million worldwide. Reviews were also good, while some critics had problems with the more action-oriented approach to the story rather than the slow, heartfelt one taken with the first film. The use of computer generated imagery and effects told the story the way the animators had seen it, and it was a blast to experience. It is also the first Disney animated feature to be exhibited in IMAX theaters.

Warner Bros. becomes to the first big competitor to the reborn Disney, just as they were the big competition to Disney during the Golden Age, with the release of Richard Williams' The Thief and the Cobbler, featuring dazzling animation all painstakingly done by hand. Critics gush over the visuals, but also criticize the often stuffed story and lack of heart. Regardless, it is a milestone for feature animation. It opens the same day as The Rescuers Down Under and puts up a good fight, grossing $102 million domestically and $244 million worldwide. Disney takes note of this and retools Aladdin to be more of an irreverent comedy. It was the first head-to-head match in the world of animation, and it receives widespread coverage all across the board.

The New Golden Age Continues...

Disney continues to deliver box office smash after box office smash. Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King are all massive hits and are nominated for Best Picture each time out. Warner Bros. successfully competes with Disney. Paramount invests in an animation studio called DreamWorks, spearheaded by an enthusiastic Paramount executive Jeffrey Katzenberg alongside Steven Spielberg. Michael Eisner is also involved, also from Paramount. Other studios like Fox get off to a rough start, with films that are either rushed in response to Disney's or are too kid-friendly to appeal to the mass market. The animation world continues to change and change by the mid-1990s... For the better...

~

If Don Bluth were to stay with Disney during the late 1970s and early 1980s and help usher a new Golden Age, how would you think it would happen? Would your portrait of Disney with Bluth on board be optimistic? Or would it lead to more troubles with the executives. My take on this is unabashedly positive, as I do believe Bluth along with the enthusiastic young animators at Disney, were going to be able to get Disney animation back on the map and start the Renaissance long before the late 1980s.

What would your alternate history be like?